A Brief Herstory of Gum Shoe Gals, Spy-Fi Sheroes, and Private Dick Chicks: Part Four

Jennifer K. Stuller on April 7, 2011 in Uncategorized 7 Comments »The Never-Before-Seen Conclusion! (Catch up with parts One, Two, and Three – They have video!)

Popular culture is a fantastic place to explore ideas and assumptions about gender, and because I’m a firm believer that questions are the content, before I close, I want to reference those I posited at the beginning of this presentation, now that we have some context.

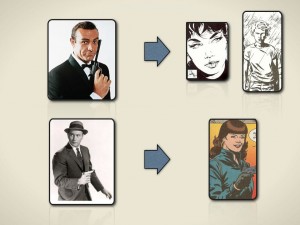

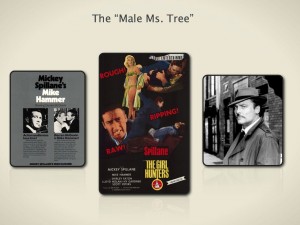

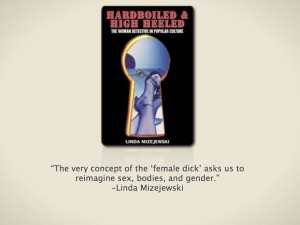

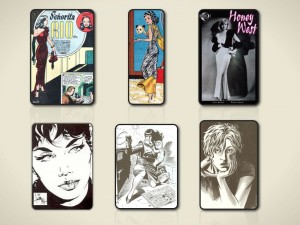

If male characters define the archetypes of Spy and Detective, what does it look like when women fill those roles? And are these female characters simply superimposed on to their male source material?

Greg Rucka has said that while gender is an element of character, gender is not character itself – and that while he treats his female characters the same way he treats his male ones there is a difference in how he writes them.

He asserts that if he wrote a female character the same way he wrote a male one, then she wouldn’t be female, she’d be a guy who looks like a girl with a girl’s name.

And a female character is not, in his words, “a guy with tits.”

The next was: is the idea that they are possibly female versions of male characters a gimmick? Or does the fact that they are unconventional bodies in traditional positions mean that they are capable of challenging assumptions about gender? And does that make them feminist?

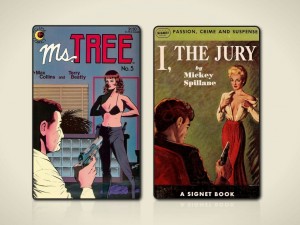

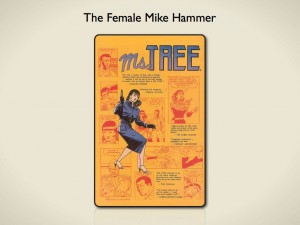

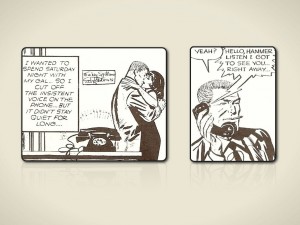

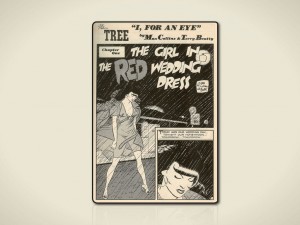

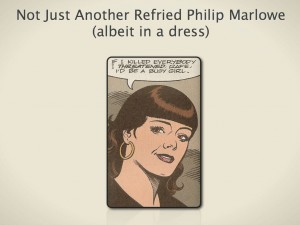

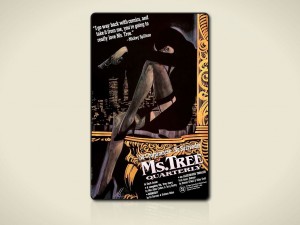

What about a “female Mike Hammer”? Sure sounds like a gimmick.

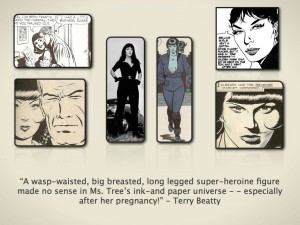

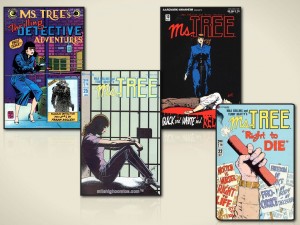

And yet, as Collins has said, one of the interesting aspects of writing Ms. Tree is that all he had to do was let her do things men routinely did in this kind of story – meaning a pulpy detective tale – and a special resonance would be created.”

Which does reinforce the idea that unconventional bodies in traditional roles are capable of challenging assumptions about gender, simply by being there.

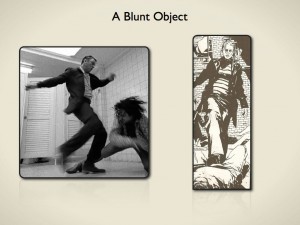

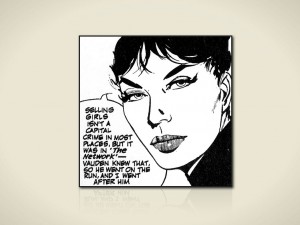

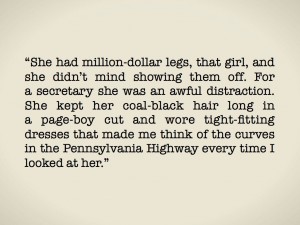

But because sex and subterfuge are inseparable from the spy fiction and detective genres, even when female agents use the same fighting skills and weapons as the opposite sex, the addition of their sexual appeal makes them deadlier than the male.

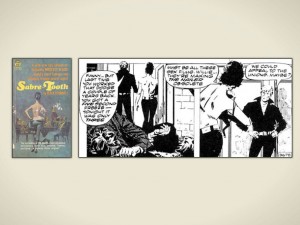

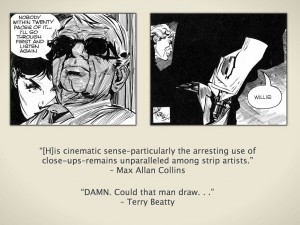

For example, Modesty has a trademark technique called “The Nailer” – where she walks into a room full of criminals topless, effectively stunning them, while Willie sneaks round from behind to take them down.

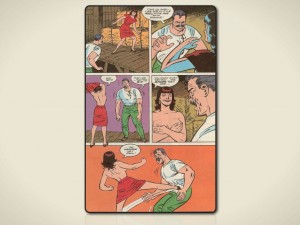

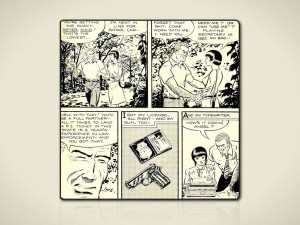

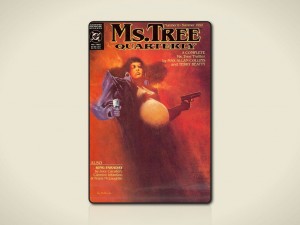

Ms. Tree, in a nod to the cover of Mickey Spillane’s I, the Jury – as well as to Modesty, distracts a villain in nearly the same way.

And it worked so well the first time that she did it again.

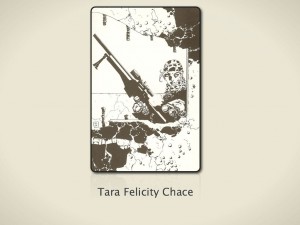

Tara, in a more subtle fashion, manipulates a border crossing in potentially hostile territory by pretending to accidently hand over a nude photo of herself with her papers.

So we can assume, at least with these 3 character examples, that women in unexpected roles are capable of BOTH subverting and reinforcing assumptions about gender.

Finally, why a female – and is she feminist?

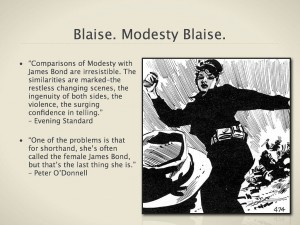

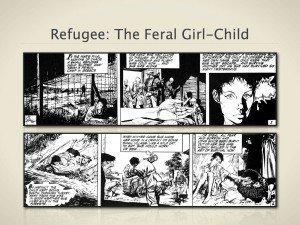

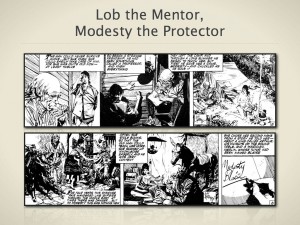

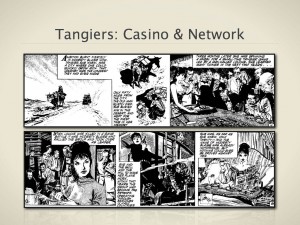

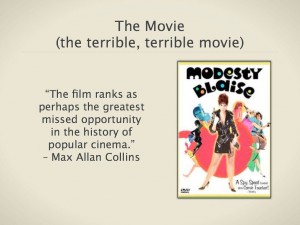

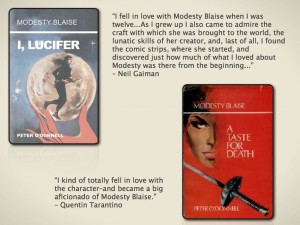

Modesty Blaise, who was often, and erroneously compared to James Bond, was created by O’Donnell to counter the preponderance of “big,” . . . “male,” . . . “superheroes.” And has himself has said, she is the antithesis of Bond.

A female character with all the skill and excitement of a “Bond”- type, but that has little to do with him, is not modeled on him, and is the protagonist of a series that ran successfully for over 40 years, is certainly feminist indeed.

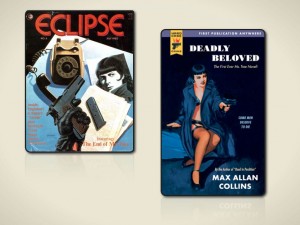

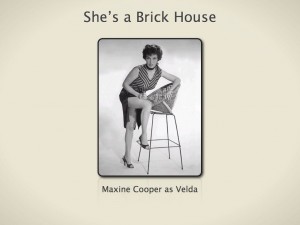

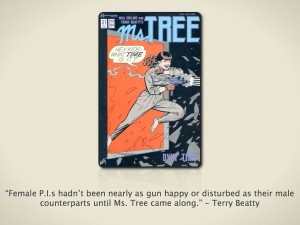

Of Ms. Tree, Max Allan Collins has said that she was, and is, a feminist in the sense that she is a strong woman who makes her own decisions.

He didn’t want to do the typical role reversal story in which the female hero is depicted as tougher, smarter, and more athletic than the men around her – feeling that an approach of that nature was inherently sexist. And he wanted equality for his female protagonist.

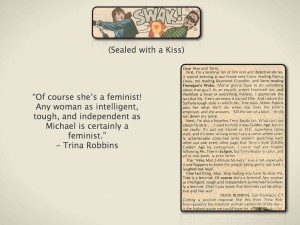

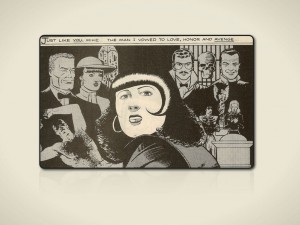

Of course, one Ms. Trina Robbins recognized Michael as a feminist early on. In a missive to Beatty and Collins’ letter page, she writes, “Any woman as intelligent, tough, and independent as Michael is certainly a feminist.”

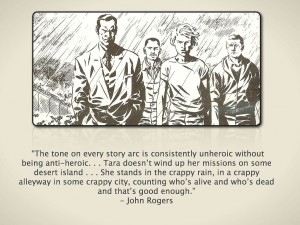

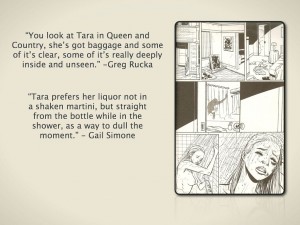

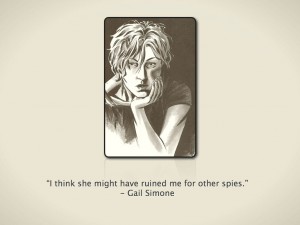

Tara, is a highly trained, intelligent, and skilled agent. She’s also realistically depicted as having a complex emotional life. She’s depicted as physically beautiful – as most female heroes are – but Rucka has noted that “she’s never more attractive than when she’s being smart, when she’s doing her job, and doing it well.”

It’s a welcome rarity in spy fiction for a woman’s actions and intelligence to be emphasized over her appearance.

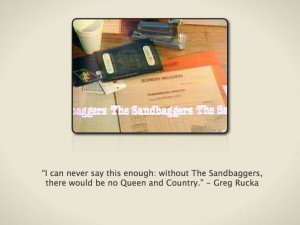

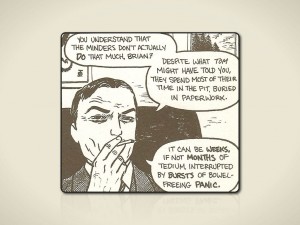

Queen and Country is more than a simple role reversal story, a woman in a man’s place. As Rucka has said, one of the reasons he loves writing female characters is that “situations and stories that we have seen thousands of times before, become entirely different if you recast your protagonist as female, because dynamics change.”

So while these women ARE rooted in, based on, or frequently referenced in relation to male characters, they are not merely female imitations.

They are anti-Bonds and female dicks.