In 1960s Britain, even before the Bond Phenomenon was

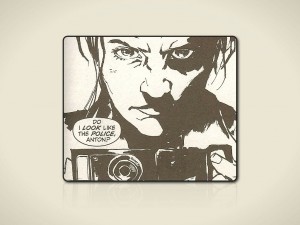

ignited by film adaptations of Ian Fleming’s novels about a rakish secret government agent, a spy-fi woman was kicking ass in a daily news strip. She dealt in espionage, but never worked in an official capacity, preferring instead to handle matters on her own terms.

This woman was the extraordinary Modesty Blaise.*

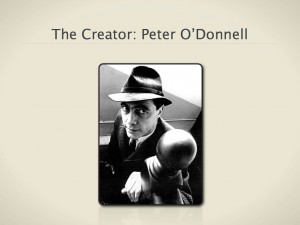

At the same time the producers of the then-fledging British television series, The Avengers, recognized that the time was ripe for a female adventurer of complexity, independence and sexual sophistication – which we saw in Honor Blackman’s Dr. Catherine Gale – O’Donnell was thinking on a serendipitous wavelength. His spy-fi creation, Modesty Blaise, debuted in England in 1963 and appeared in newspaper strips and novels for over 40 years; all written by O’Donnell himself.

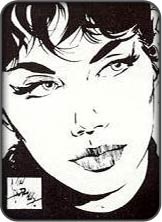

Modesty is a survivor, a force of nature, an ex-crime boss, and a loyal friend. She was born out of glamour girl news strips and British espionage stories—but Modesty is neither a nearly-naked ditz, nor, as she has often been called, a “female Bond.” She is one of the great literary characters of the 20th Century. And yet, though she has both subtly infiltrated—and overtly influenced—European and American popular culture, and was a groundbreaking and progressive character that rivaled the other spy-fi icons she was so often compared to, the name, Modesty Blaise, remains practically unknown to an American audience; and is increasingly distanced from a British one.

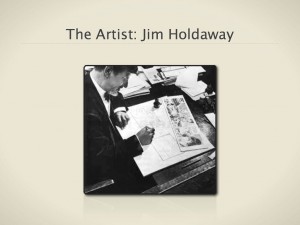

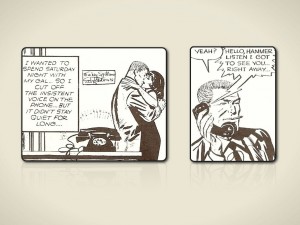

Prior to her debut, O’Donnell wrote other newspaper strips, as well as romantic serials for women’s magazines.  In the mid-1950’s, he was hired alongside Jim Holdaway—a former advertising illustrator, to take over work on Romeo Brown—a detective strip that frequently featured women in various states of undress and who were much in the tradition ofNorman Pett’s, Jane (1932-1959). O’Donnell and Holdaway collaborated on the title for seven years, and became close friends in the process.

In the mid-1950’s, he was hired alongside Jim Holdaway—a former advertising illustrator, to take over work on Romeo Brown—a detective strip that frequently featured women in various states of undress and who were much in the tradition ofNorman Pett’s, Jane (1932-1959). O’Donnell and Holdaway collaborated on the title for seven years, and became close friends in the process.

In 1962, O’Donnell was asked by the Daily Express to create an original strip for their paper. For the project he was interested in bringing the two genres he had been working in together; “big superhero types” like Garth and Tug Transom, combined with the stories he wrote for the women’s market. Like William Moulton Marston before him, who created the character of Wonder Woman to counter the preponderance of “big,” “male,” “superheroes,” O’Donnell observed that the time was ripe for an audience to be receptive to a feminine woman who would be as good in combat as any male—often better—though unlike Marston his creative choice seems to have been made out of playful ingenuity rather than a sociopolitical agenda.

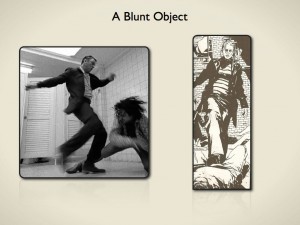

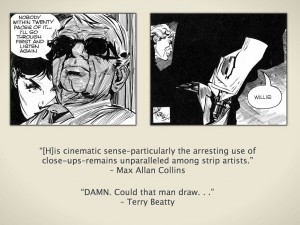

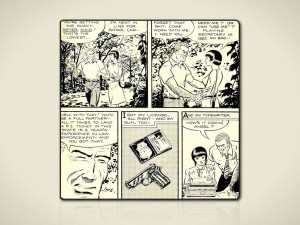

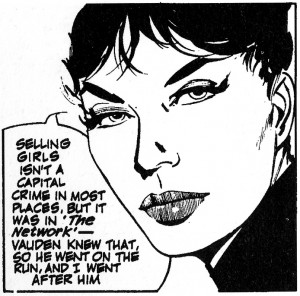

O’Donnell scripted the first 8 weeks of a story arc for his female adventurer and artist Frank Hampson, of Dan Dare fame, was hired to draw the strip. Though talented, Hampson thoroughly misinterpreted the character. Modesty looked like a grown-up girl sleuth, when she needed to be naughtier, more exotic, and less British. O’Donnell convinced the Express that Holdaway would be a more appropriate artist.  He was, and his work has long since been praised by writers, artists, and critics for his masterful and cinematographic use of black and white.

He was, and his work has long since been praised by writers, artists, and critics for his masterful and cinematographic use of black and white.

When the strip was ready to print, the Express backed out at the last minute when someone came to the conclusion that the exploits of a “woman of the underworld” wasn’t appropriate material for a family oriented newspaper. Fortunately, Charles Wintour, an editor at the Evening Standard, picked up Modesty Blaise for his paper, where the strip stayed for 38 years.

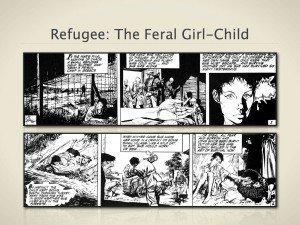

O’Donnell believed that Modesty’s character had to be ingrained in her bone; that she would have experienced a childhood of struggle, yet had an innate will to survive. Her backstory was inspired by an encounter O’Donnell had with a young female refugee while he was stationed in Persia during World War II. His unit had shared some food with what appeared to be an orphaned child, and even provided rations for her tiny traveling bundle. She gave thanks and went on her way, all of age twelve, and all alone. O’Donnell never forgot her, and it was this girl’s brave spirit he channeled into Modesty’s fictional past.

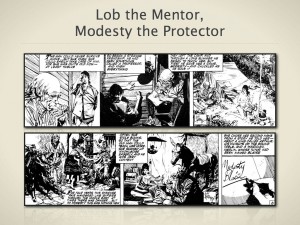

Modesty Blaise, then, is a refugee from Hungary, whose parents were killed—a tragedy that resulted in amnesia for the homeless child. She traveled alone for over a year until she met a Jewish man in his fifties named Lob at a displaced persons camp. Lob had been a professor in Bucharest prior to the war and though intellectually brilliant, he wasn’t equipped to protect himself from the threat of other, more desperate refugees. The wild child took him under her protection, and they traveled the Middle East together. She provided food and safety. He gave her an education, and her name, Modesty; which was given in irony to a girl who held no shame about her body, naked or clothed. Her last name she gave herself, Blaise, after Merlin’s tutor from the Arthurian legends. Lob died when Modesty was 17. She buried him in the desert and moved on, once again alone, to the city of Tangiers.

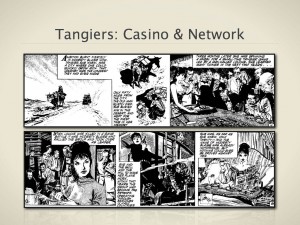

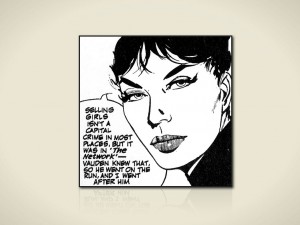

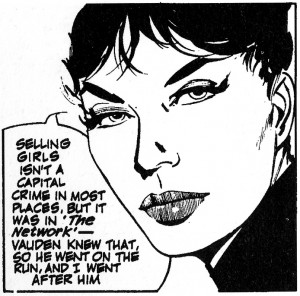

For two years she worked the roulette table at a casino in Tangiers owned by a man named Henri Louche, who also ran a crime gang. On the night of Louche’s murder by a rival gang, a 19-year-old Modesty took over his organization. She rallied Louche’s employees and built up the small time gang into a global syndicate called, “The Network.” But while the underworld was their playground, Modesty had her own sense of morality, which governed their dealings. She made sure The Network never dealt in vice; those who disobeyed this rule through the sale of drugs, women, or children were either delivered to the authorities or their graves.

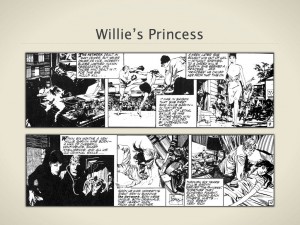

While in Saigon on Network business, Modesty came across a man named Willie Garvin who became Modesty’s right arm in The Network, and her closest companion. “Princess” was what he, and he alone, would always call her.

On a side note, O’Donnell’s introduction to Titan’s 2004 reprint of his first Modesty Blaise strip story, “La Machine,” tells how he was looking for somebody to give Jim Holdaway as a model for the physical appearance of Willie Garvin. One evening he was watching a televised performance of the play, “Hobson’s Choice” and thought of one of the actors, “[T]his bloke would do good for looks.” The next morning O’Donnell called the BBC and asked for the agent of the man he’d seen, hoping he could sit in as a model. The actor was Michael Caine.

The response from the operator at the BBC was, “Michael who, was that?”

The response from the operator at the BBC was, “Michael who, was that?”

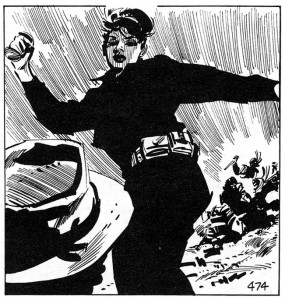

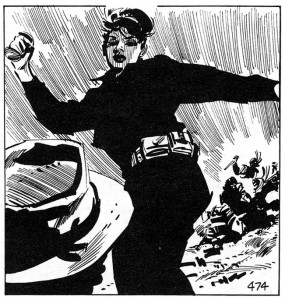

O’Donnell has said that “Modesty and Willie aren’t superheroes, they don’t always get things right and they can end up in a hopeless situation.” But, as any reader can see, they are “fantastic”—especially when you start to add up their varied talents. Modesty is adept in both armed and unarmed combat, often employing obscure and concealed weapons. She is compassionate, yet has a capacity for ruthlessness that is tempered only by her sense of justice. She will kill anyone who hurts a friend. She is a self-proclaimed “compulsive payer of debts,” and has a progressive attitude towards race, class, and spiritual beliefs. And Modesty rewards loyalty; upon dissolution of The Network in order to retire at age 26, she made sure each of her employees would receive either a pension or a branch of the organization.

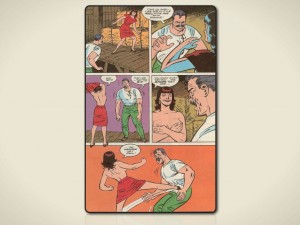

Modesty is completely comfortable in her skin, whether she’s fighting, nude, or fighting while nude. She is fully present in her body, recognizing it as a source of pleasure, a weapon, and a gift to give. The most infamous way that Modesty’s body, sexuality, and confidence come together as perfect weapon is in a technique she calls, “The Nailer” –a particularly action femme move. (Though it should be noted that seduction is only one of many of Modesty & Willie’s tools. They both do it, but it’s not their only skill, as is often the case with vixens, femme fatales, vamps, and lotharios.)

The Nailer involves Modesty stripping to her waist to reveal her lovely, bare breasts, while Willie sneaks around back of whomever it is they’re set to take down. Modesty walks into the room, the men are stunned, a few extra seconds are bought that enable Willie to chill them—the villains are Nailed.

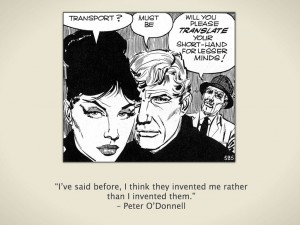

Willie Garvin is an expert with knives, crafting them himself, along with all of the pair’s requisite spy gadgets. He always wins at cards, can bend steel with his bare hands, and is mildly precognitive. He can quote at length from the Bible, having spent a year in prison with only a Psalter to read. He also speaks Pidgin English and can mimic voices to perfection.

Willie Garvin is an expert with knives, crafting them himself, along with all of the pair’s requisite spy gadgets. He always wins at cards, can bend steel with his bare hands, and is mildly precognitive. He can quote at length from the Bible, having spent a year in prison with only a Psalter to read. He also speaks Pidgin English and can mimic voices to perfection.

Modesty and Willie have one of the most unique relationships in popular culture, and their humanity and friendship are the foundation of their adventures. They’re soul mates; inseparable and symbiotic. They trust and know one another completely, but they aren’t lovers. They’ve never indulged in a sexual relationship—never will. And unlike Steed and Peel, or Mulder and Scully, we want it that way. Their friendship is a large part of what makes them compelling.

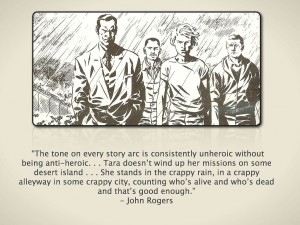

The deadly duo work hard, taking out dangerous criminals, drug dealers, and diabolical masterminds through a combination of martial arts, money, connection & influence, ingenuity and verve. But they also play hard—a tough caper might be alleviated by a turtle race in the ocean, or perhaps a go-cart ride at dawn. Few have the skills to live so confidently—and the world truly is the oyster of Blaise and Garvin.

The pair have been called “criminals with hearts of gold,” a description which is only partly true, as when we first meet them, Modesty and Willie are retired from crime. More accurately, they’ve always walked a fine line between criminality and heroism—always leaning towards the moral side, if not necessarily the legal one.

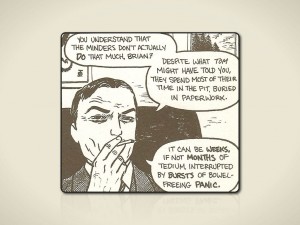

Sir Gerald Tarrant, of the British Secret Service, was savvy enough to recognize that the pair wouldn’t be content to remain idle, and that they could be an asset to Her Majesty’s government. But Modesty is no one’s agent, and where she goes Willie follows. They do help Sir Tarrant out, personally and professionally, but never in an official capacity. And they are grateful to him for helping them realize they need adventure every now and then; they crave danger, intrigue, problem-solving, and hand-to-hand combat. It’s who they are.

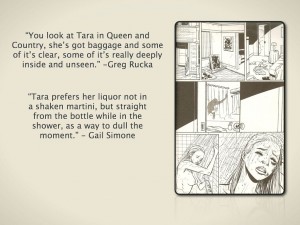

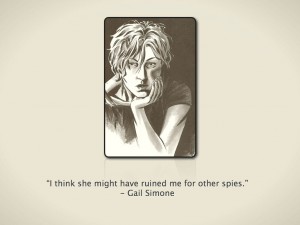

As mentioned already, Modesty has frequently, and erroneously, been referred to as “the feminine answer to James Bond.” The Evening Standard once wrote that “Comparisons of Modesty with James Bond are irresistible. The similarities are marked—the restless changing scenes, the ingenuity of both sides, the violence, the surging confidence in telling.” But these are superficial similarities; part and parcel of the genre, and those who claim that Modesty is a female James Bond—which O’Donnell has firmly stated is “the last thing she is” thoroughly misunderstand his creation. Modesty is the antithesis of Bond.

One must of course acknowledge, as O’Donnell does, that Bond is a worthy icon, but “he only exists for the period of the mission he’s on—he doesn’t have a home, interests, friends.” Indeed, while Bond has a residence, a housekeeper, silver and china, he’s indifferent to comforts which give others pleasure or a sense of security—the sensations of living. He may play cards, sleep with beautiful women, and indulgently imbibe, but one gets the feeling he couldn’t care less about any of it. Modesty, on the other hand, is capable of truly experiencing the moment. She enjoys her luxuries, as much as she enjoys sharing them. As O’Donnell notes, unlike Bond, “she’s got a small circle of close friends . . . interests and . . . a life that goes on in the background and is interspersed with, not missions, but events that she falls into for one reason or another.”

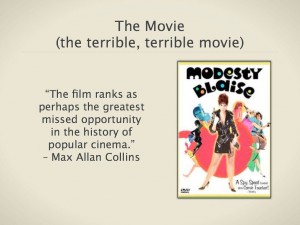

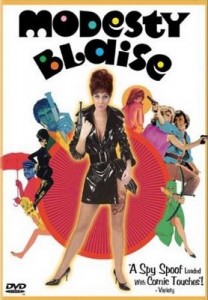

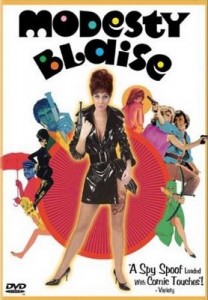

Over the years Modesty Blaise has branched out into other media. A terrible, terrible movie, directed by Joseph Losey, was released in 1966. O’Donnell claims it makes his nose bleed just to think of it. Indeed, the failures of the 1966 Joseph Losey film are legendary; characters are miscast, misread, and misrepresented. Fight scenes are poorly choreographed; stunt doubles are embarrassingly obvious. The ultimate offense was, the quality of the material O’Donnell created certainly had the potential to rival the Bond franchise. If the movie had stayed true to character, tone, and genre, Modesty Blaise could have been as well known. But the Joseph Losey film single-handedly prevented the property from reaching an American audience—one which was already in the midst of a profitable spy craze.

Over the years Modesty Blaise has branched out into other media. A terrible, terrible movie, directed by Joseph Losey, was released in 1966. O’Donnell claims it makes his nose bleed just to think of it. Indeed, the failures of the 1966 Joseph Losey film are legendary; characters are miscast, misread, and misrepresented. Fight scenes are poorly choreographed; stunt doubles are embarrassingly obvious. The ultimate offense was, the quality of the material O’Donnell created certainly had the potential to rival the Bond franchise. If the movie had stayed true to character, tone, and genre, Modesty Blaise could have been as well known. But the Joseph Losey film single-handedly prevented the property from reaching an American audience—one which was already in the midst of a profitable spy craze.

A good thing did come out of the movie. O’Donnell was able to use the story he had done for the original film script for the first in what would become a series of 11 novels and 2 collections of short stories detailing Modesty and Willie’s capers, exploits, and adventures—even their demise. The final collection of short stories came out in 1996 and was titled, Cobra Trap, which was also the name of what O’Donnell imagined as the final story for Modesty and Willie. He wanted to create a suitable end for the pair, and didn’t want their fate to end up in the hands of another writer. And who can blame him? They had been his companions for forty years. O’Donnell sets the story far in the future and says of his choice, “I concluded that they would want to go out doing something really useful, not saving the world James Bond-style, but something on a small scale that was worth doing, saving lives in way, and together. . . Quite a number of fans haven’t been able to bring themselves to read that last story . . . those who have usually say that it was right; it was the suitable ending for them. It was the kind of ending that they would have wanted.” I can tell you it was.

On a side note, while writing the Modesty strips & novels, O’Donnell was also writing a series of romance novels under the pseudonym, Madeline Brent. The true identity of “Ms. Brent” remained a secret until the mid-1990s.

On a side note, while writing the Modesty strips & novels, O’Donnell was also writing a series of romance novels under the pseudonym, Madeline Brent. The true identity of “Ms. Brent” remained a secret until the mid-1990s.

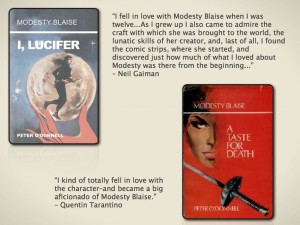

Since the original Modesty Blaise fiasco, several prominent creators of popular culture have expressed interest in making a filmic adaptation that would remain truer to its source. Sandman creator Neil Gaiman has glowingly said, “I fell in love with Peter O’Donnell’s astonishing heroine, Modesty Blaise, when I was twelve,” adding that as he grew up he “also came to admire the craft with which she was brought to the world, the lunatic skills of her creator, and, last of all, I found the comic strips, where she started, and discovered just how much of what I loved about Modesty was there from the beginning….”

Gaiman wrote a treatment for the novel, I, Lucifer, and apparently even started actual script work. Luc Besson was rumored to direct the picture.

Gaiman wrote a treatment for the novel, I, Lucifer, and apparently even started actual script work. Luc Besson was rumored to direct the picture.

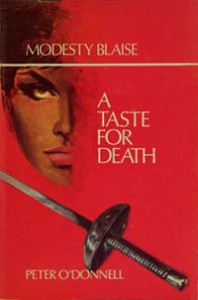

Quentin Tarantino, a long-time fan of Modesty Blaise, was rumored to direct the film version of another novel, A Taste For Death—an intense, emotional, improbable, paranormal, and wicked deadly story that would have been a fitting venture for the frenetic auteur—but unfortunately the project has never come to fruition.

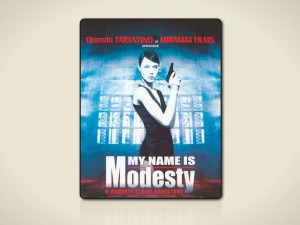

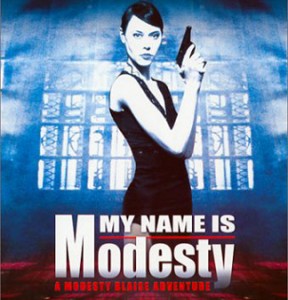

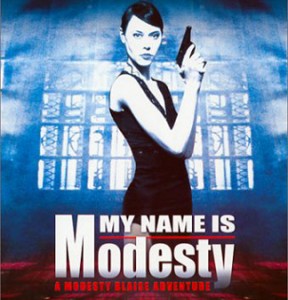

Tarantino, however, was tangentially involved in the B-movie, My Name is Modesty, directed by his occasional cohort, Scott Spiegel. The movie is an original story, which O’Donnell was consulted on, that centers on the night Henri Louche is murdered at his casino and how a young Modesty manages to save a group of hostages from similar demise. Alexandra Staten plays a convincing Modesty by conveying the essential characteristics we’d hope to see in a filmic embodiment; compassion, resolve, wile, bravery, and yes, of course, ass-kicking.

Spiritual Descendents

Once established in their respective media, Cathy Gale and Modesty Blaise no doubt influenced each other—but what’s especially interesting is that they emerged at nearly the same time. It was a cultural moment; a zeitgeist collision of changing social values which were reflected in popular culture. Women’s lib was around the corner, and subsequent representations of extraordinary women in modern mythology would be modeled after Cathy, Mrs. Emma Peel, and Modesty. These women combined intelligence, femininity, independence, and agency with confidence in their sexuality and a sophisticated style.

Their legacy deserves some attention, Modesty’s in particular, because she is so little known, yet has had such a wide influence. Therefore her contribution to a pop culture lineage of spy-fi superwomen will receive special attention in the following paragraphs.

Ms. Diana Prince

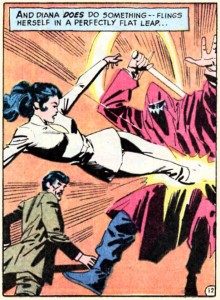

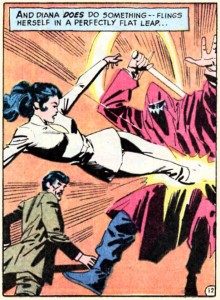

Members of the team of writers and artists who worked on Wonder Woman during her Spy-Fi era (Issues 178-204) have acknowledged that Mrs. Peel’s style was inspiration for the mod direction taken with the new Diana Prince, and this is most evident in her hairstyle, her Emmapeelers, and in her partner I Ching’s bowler and brolly.

But the spy era issues show that Diana has a striking amount of Modesty in her as well. Definitive evidence that images, story arcs, or characteristics were borrowed from Modesty Blaise are difficult to come by but those in the American comics industry would likely have had access to reprints of British strips—no matter obscure they may have been in the States. A few examples are in order because while the physical style may be Peel, the attitude can, at times, be very Blaise.

But the spy era issues show that Diana has a striking amount of Modesty in her as well. Definitive evidence that images, story arcs, or characteristics were borrowed from Modesty Blaise are difficult to come by but those in the American comics industry would likely have had access to reprints of British strips—no matter obscure they may have been in the States. A few examples are in order because while the physical style may be Peel, the attitude can, at times, be very Blaise.

Like Modesty, Diana works outside of the law and will kill if she feels it’s just.

She uses yogic trances to preserve her resources—which is a technique Modesty learned from her guru, Sivaji; and she travels the world much like the globally sophisticated Blaise, while Peel remained in the UK.

Maybe O’Donnell directly influenced Mike Sekowsky and Denny O’Neil—he certainly inspired other mythmakers. But perhaps a definitive answer to the question is irrelevant when popular culture is so porous.

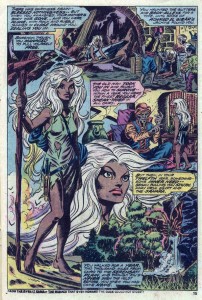

Ororo Munroe (a.k.a Storm)

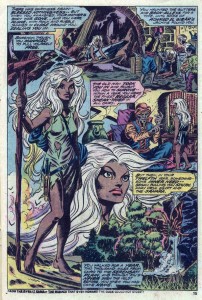

The influence is much clearer with Ororo Munroe. X-Men writer Chris Claremont has shrugged off his appropriation of Modesty’s origin story for the character of Storm by saying “If you’re going to swipe, swipe from the best.”

In Uncanny X-Men #102, we learn that Ororo, like her spiritual ancestor, was an orphan who traveled alone and by foot, until meeting up with a man who would become her mentor. (But while Lob was a scholar, Achmed el-Gibar was a master thief.)

In an article for Back Issue, Peter Sanderson suggests that “Modesty Blaise is the prototype for today’s female action heroes” and that “it should be no surprise that Modesty Blaise was an important influence on Claremont’s own depictions of independent, capable, heroines.”

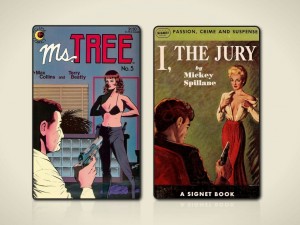

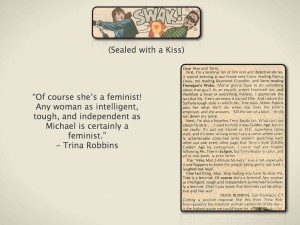

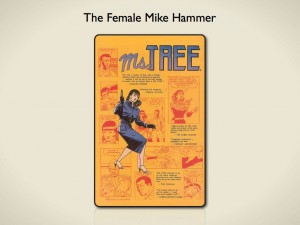

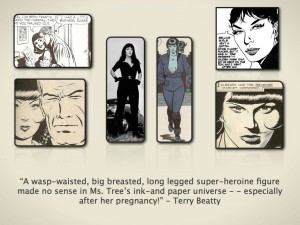

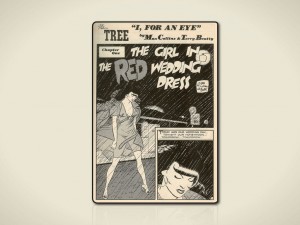

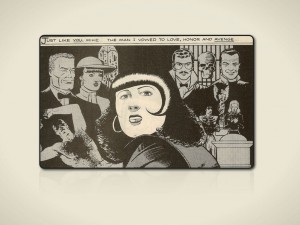

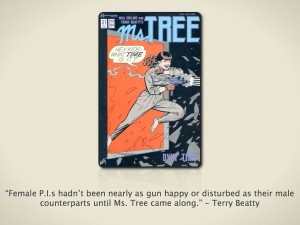

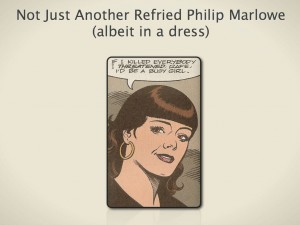

Ms. Tree

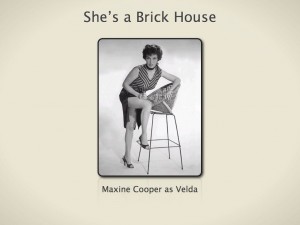

Ms. Tree ran non-stop for fifteen years, making it the longest running detective comic book of all time. Max Allan Collins based the initial story on the idea that Mickey Spillane’s P.I., Mike Hammer, finally married the gun-packing, tough-as-nails Velda. Collins, who co-created Ms. Tree with artist Terry Beatty explains:

“The central notion was that the tough private eye and his loyal secretary, his unrequited love for years and years, would finally get married, only for the P.I. to be murdered on their wedding night, leaving the secretary to take over the detective agency and step into her late husband’s shoulder holster. The private eye’s murder would be the former secretary’s first case.”

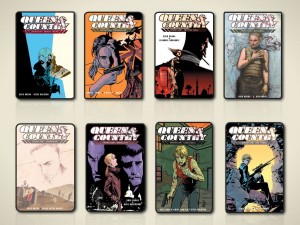

Collins notes that the character of Ms. Tree owes a nod to Modesty as well. He and Beatty were intrigued by the idea of “An American Modesty Blaise” for their detective series, who would be to private eyes what Modesty is to spies.

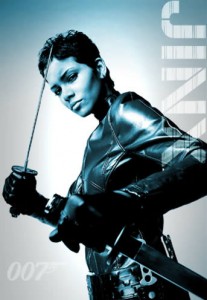

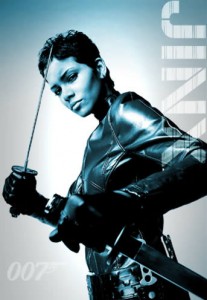

Jinx

In Die Another Day (2002) Halle Berry starred as “Jinx,” a role that director, Lee Tamahori, says he modeled on Modesty Blaise in hopes the character would be “as kick-ass as Bond.” Unfortunately, the result was a poor excuse for a Modesty wannabe, rather than a unique, or even intriguing, homage.

In Die Another Day (2002) Halle Berry starred as “Jinx,” a role that director, Lee Tamahori, says he modeled on Modesty Blaise in hopes the character would be “as kick-ass as Bond.” Unfortunately, the result was a poor excuse for a Modesty wannabe, rather than a unique, or even intriguing, homage.

The Bride & Kill Bill

Though A Taste for Death never reached production, Tarantino’s love of Modesty was clearly subsumed into the character of Beatrix Kiddo—also known as “The Bride” in Kill Bill. In Kiddo, we see Modesty’s intention, ingenuity, and controversial justice. (Plus, lot’s of killer sword fighting.)

Uma Thurman’s Bride succeeds where Halle Berry’s Jinx failed—Kiddo is a compelling homage. She’s Modesty in her guts; unafraid, undeterred, and always stylish.

************************************

The following examples, like Diana Prince, are unconfirmed descendents, but also likely candidates. Regardless of whether or not Modesty directly influenced these superwomen, she certainly influenced the Spy-Fi genre, and is therefore still a spiritual predecessor to them.

Mathilda

When thinking of female orphans who are innate survivors it makes sense to suggest that “Mathilda”—from Luc Besson’s 1994 film Leon (also known as The Professional)—may be a spiritual relative of Modesty.

When thinking of female orphans who are innate survivors it makes sense to suggest that “Mathilda”—from Luc Besson’s 1994 film Leon (also known as The Professional)—may be a spiritual relative of Modesty.

Observation is the only formal evidence of this. But we do know from Besson’s collaboration with Moebius and Mezieres on The Fifth Element that he is familiar with comics, and as mentioned, the director was rumored to be linked to the I, Lucifer project so he is clearly familiar with Blaise.

Played by a very young, sultry and precocious, Natalie Portman, Mathilda, like Modesty, is fierce, resourceful, cunning, and brave. From the start of their respective quests, both are young girls who don’t just survive –which is a laudable feat unto itself–but seek out and master skills that will make them survivors. They are sexually confident, and combine compassion with the ability to exact just revenge. It’s quite easy to see Mathilda growing up to be a woman very much like Modesty.

Lara Croft

Angelina Jolie’s Lara Croft is Modesty incarnate. She’s wicked, rich, beautiful, and shameless. An orphan, a woman of leisure, and a seeker of treasure, Lara, like her spiritual predecessor thrives on danger.

The most obvious Modesty Blaise Moment arrives early in the movie, when we see that Lara, like her spiritual ancestor has an admirably healthy lack of shame. Lara has just taken a shower and her man-servant, Hilary, greats her with a towel and a very feminine sundress.

Lara Croft: Oh… very funny.

Hilary: I’m only trying to turn you into a lady.

Lara Croft: Mm…

(She drops her towel as she walks past him, completely nude, and into her wardrobe)

Hilary: (sighs) And a lady should be modest.

“Yes” replies a mischievous Lara, “a lady should be modest.” (Lara Croft: Tomb Raider)

The two women both exude a combination of sass, confidence, sex and danger.

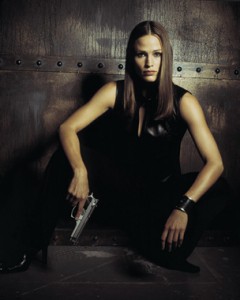

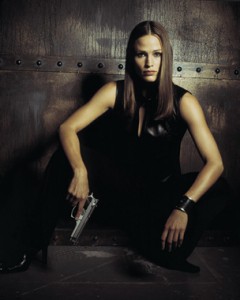

Sydney Bristow

Sydney Bristow is the daughter of two spies. One is an agent for the CIA, the other worked for the KGB. But she is also the spiritual daughter of Modesty, Cathy, Emma, Honey and Pussy, as the quintesstial feminine spy-fi characteristics established by Bond, The Avengers et. al, have seeped into popular consciousness establishing precedents which have then descended to her.

Sydney Bristow is the daughter of two spies. One is an agent for the CIA, the other worked for the KGB. But she is also the spiritual daughter of Modesty, Cathy, Emma, Honey and Pussy, as the quintesstial feminine spy-fi characteristics established by Bond, The Avengers et. al, have seeped into popular consciousness establishing precedents which have then descended to her.

Sydney, like Modesty and Cinnamon Carter, skillfully uses her body as a tactical distraction. In fact, she frequently used variations on Modesty’s “Nailer” technique. For example, in the series Season Four opener of Alias, “Authorized Personnel Only,” Sydney, who has “accidentally” been booked in the same sleeping cabin as her mark on a train, emerges from the bathroom clad in a white negligee. With a blonde wig and Swedish accent she forces his focus to her, and her alone, as she coos in broken English, “Is dis okay for me? I just got it.” It’s not a full-on bare-breasted stunner, but her physical beauty and hypnotizing sexuality perform the same function. They’re arresting, and her audience is nailed.

Alias plays with the genres that O’Donnell combined to create Modesty Blaise—the concept of a superhero, or at the very least, a superwoman, with romance and high drama. Syd is much more emotionally volatile than the cool, cool Modesty, but they do share a fierceness not to be reckoned with. It was inevitable that Modesty aficionado Tarantino would write and star in a number of episodes. In 2002, he told Rolling Stone that, “Alias delivers what The Man From U.N.C.L.E. always promised. It actually lives up to the coolness of its potential.” The author of the piece, a profile on Jennifer Garner, noted that while the actress has a stunt double (Shauna Duggins) she also does most of Sydney’s fight sequences herself. He writes, this can be much trickier when you’re showing off cleavage and that “it brings to mind the old quote about how Ginger Rogers had to do everything Fred Astaire did, only backward and in high heels. Likewise, Garner is Jackie Chan in a slinky cocktail dress.” (Rather than commending her talents by comparing her to a talented male, let’s just acknowledge that Garner kicks ass—backwards and in heels.)

The rare and admirable accomplishment of Alias was that it could show Sydney in any number of dominatrix wear, school-girl outfits, rubber dresses, wigs, sexy librarian glasses, thigh-high boots, high-heeled shoes, and high-tech catsuits and not have it detract from her power. Sexuality may have been her weapon, but it was never her source. Her aliases were a playful nod to genre conventions, but it was also stressed that Sydney was a well-trained government agent. Athletic, intelligent, skilled in various martial arts and weaponry (which, unlike Rigg, Garner actually trained for) and fluent in at least a dozen different languages, Sydney had friends, was a kick-ass mom, a kick-ass daughter and had an admirable sense of justice, compassion, and integrity. Unlike many of her spiritual predecessors, Sydney Bristow was allowed a multi-dimensionality that made her sexuality just a part of her—rather then the reason for her being.

Admittedly, marketing to a heterosexual male audience could not be completely avoided. When Garner became pregnant, she wanted to go undercover as a “big, fat, man.” Despite her pleas, the producers refused. And as Leigh Adams Wright, points out in her contribution to Alias Assumed: Sex, Lies and SD-6, “there’s a difference in the ways men and women on Alias perform their espionage duties. Vaughn never has to flirt with the door guy; Dixon may have to wear dreads once in a while, but he’s always fully clothed.” She adds that, “It’s only Sydney and her fellow female agents who end up parading around half naked and charming their way past high-tech security systems into top-secret labs . . . feminine wiles are a favorite weapon in the Alias female spy’s arsenal.”

**************

In the interplay of popular culture, of new ideas and borrowed ones, of zeitgeists, cultural trends, swipes, homages, and amalgamations, Modesty is a feminist archetype in the spy genre, as well as a groundbreaking female action hero. In laying out where she’s come from and who she’s linked to, it’s clear that Modesty Blaise has inspired representations of phenomenal, mythic women who’ve come after her. And perhaps she can rightly be seen as a “missing link.” Like other female action heroes who are better known (at least in America; Wonder Woman, Foxy Brown, Ellen Ripley, and Buffy Summers to name a few) who have pushed the boundaries of their respective genres to further enhance the world of pop culture it is important to include Modesty Blaise in a mythical, matriarchal lineage in order to better see how porous and connected modern myth is.

* * * * *

Peter O’Donnell passed away yesterday, just 2 weeks after his 90th birthday. He died peacefully in his sleep, and is survived by his wife, children, grandchildren, and Modesty Blaise fans the world over. I will always be grateful to him for creating the most complex, resilient, kick-ass, yet compassionate, inspirational, and sophisticated female hero of all time.

Peter O’Donnell passed away yesterday, just 2 weeks after his 90th birthday. He died peacefully in his sleep, and is survived by his wife, children, grandchildren, and Modesty Blaise fans the world over. I will always be grateful to him for creating the most complex, resilient, kick-ass, yet compassionate, inspirational, and sophisticated female hero of all time.

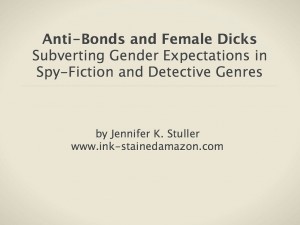

* The majority of this article was based on a presentation for the Comic Arts Conference called The Princess of Spy-Fi: A Critical and Historical Overview of Peter O’Donnell’s Modesty Blaise. Please remember and respect that no part of this may be reprinted without express permission of the author.